The Masters of Fence? Who came to your mind first?

Ridolfo Capo Ferro of Italy?

Hieronimo de Caranza of Spain?

Joseph Swetnam of England?

Richard Sheridan of Ireland?

Wait a minute … Who?

From Where?

(University of Notre Dame Fighting Irish logo)

A Broad Overview

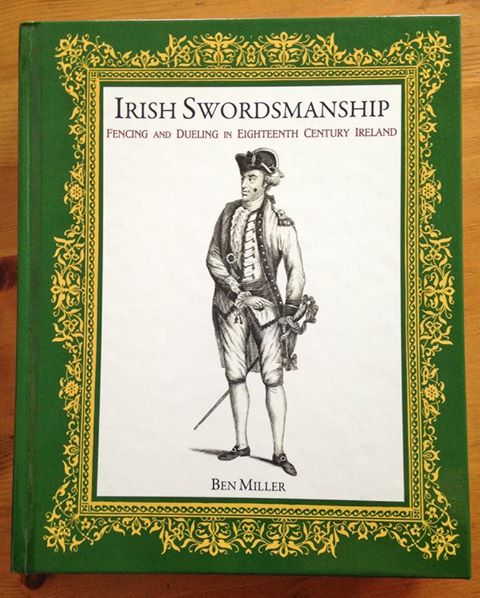

If the latter country, let alone the personality, does not resonate with a vision of civilised small sword duels or hard-fought, multi-sword-options stage fights; Ben Miller’s Irish Swordsmanship - Fencing and Duelling in Eighteenth Century Ireland will set you right.

Miller is well qualified to undertake this massive and well-documented interpretation of the subject; being both an accomplished authority in written sword lore and history; as well as also knowing what end of a sword (or pike, or bayonet) goes forward; he being a long-time swordplay student and practitioner with the eminent Martinez Academy of Arms.

“Yet, despite their obvious formidability, Irish fencers and fencing masters have found little mention in histories of swordsmanship. Their relative obscurity can be attributed to a variety of factors - including lack of self-promotion, the extremely limited state of the eighteenth century Irish publishing industry, and the fact that so very few original Irish fencing treatises -- a potential source of information on Irish masters - were published in Ireland during the era.[1]

Millars’ book goes a long way to fixing this gap in the HEMA community’s knowledge of Irish sword-related history, groups and people. And as an added bonus to the history lesson and personality profiles, he offers us his translation of a long-forgotten Irish sword instruction manual.

Chapter-by-Chapter

The content cover a multitude of subjects, some of which could be the basis for more extensive chapters of their own.

(From Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Heritage Centre Blog)

In ‘Dueling in 18thC Ireland’ we learn of the history, perceptions, characteristics, philosophy and ‘mind set’ of the Irish duelist – and a bit of geography as we're introduced to historical duelling grounds.

As to the distinguishing characteristics of the duelists themselves, it is clear that, in surveying the available evidence, what set Irish combatants apart from those in much of the rest of Europe was their remarkable psychological-emotional approach to combat - that is, their cool-headedness (termed sang-froid by the French), their indifference to personal danger, and their unshakable, devil-may-care attitude.[2]

‘Noted Irish Duelists’ gives us introductions to many of Ireland’s swordplay personalities – and the results are very much as if Brantôme had described them.

Poulett in a duel, was "said to be reckoned the best Swordsman in Europe, being capable of making the longest Longe of any Man living.[3]

‘Irish Amazons and Stage Gladiators’ highlight the adventures of four women and those ‘Maisters of Defence’ that took part in any “dangerous gladiatorial stage fight, fought with sharp weapons”. Of note, the title ‘master’ was often self-assumed, with the Masters of the Irish fencing schools considering the gladiators to be mere hackers, and there were no ‘masters’ within the ranks of the women.

The Irish gladiators known as the "Masters of the Science of Defence," … were not professional fencing masters at all, but rather … smiths, tailors, cooks, farmers, butchers, tobacconists, woolcombers, felt-makers, and printers[4]

‘18thC Dublin – Europe’s Wild West’ describes a country overrun with rural highway men and assorted criminals; and a capital in which sword-carrying, gang-related violence was the norm

‘Fencing schools & Masters in 18th C Ireland’ describes those institutions and personalities who efforts turned out swordsmen whom could hold their own against and sometimes beat the best in Europe. Here we find an interesting conundrum faced by all past and present fencing masters, who merits the title of ‘fencing master’ and who can bestow that title, and by what authority?

During the early 1780s, Dwyer repeatedly published a screed in the Dublin press, in which he touted his own training in France and disparaged the skill of local Irish fencing masters – insisting that such individuals were no fencing masters at all on account of their never having left Ireland.[5]

Miller ends his opus with his 85 page translation of, and comments on, an 1781 Irish ‘fechtbuch” the anonymously written A Few Mathematical and Critical Remarks on the Sword.

In Conclusion

Irish Swordsmanship is both a labour of love and a ten-year love of labour apparently. The breadth and detail of the easily-assimilated material that is presented (and consulted) is impressive. Nearly every chapter offers something new or long-forgotten for the historical reader to consider, and the effect of the whole is a comprehensive history of a here-to-fore, largely neglected group of HEMA peers during a specific time.

Last word: Notwithstanding that the 18th century period covered here is small-sword heavy and well after the study periods of most HEMA salles, Irish Swordsmanship is filled with facts, interesting stories and interpretations and a rare swordplay manual. There is a lot of HEMA history here that could be of interest to any student of our art, regardless of their chosen area of specialist study. I know what my home salle library is getting for Easter this year.

Last word: Notwithstanding that the 18th century period covered here is small-sword heavy and well after the study periods of most HEMA salles, Irish Swordsmanship is filled with facts, interesting stories and interpretations and a rare swordplay manual. There is a lot of HEMA history here that could be of interest to any student of our art, regardless of their chosen area of specialist study. I know what my home salle library is getting for Easter this year.

If you are interested in the current state of HEMA in Ireland; I recommend you to HEMA Ireland.

I encourage you this Saint Patrick’s Day, to dispense with the oft misused and more-often mispronounced Éire go Brách!. When joining up with your friends for the traditional festive social, try a hearty Ar do phionnsa! instead; and if any of those friends immediately go into ‘tierce’, or better yet 'prima'; that’s the buddy/'friend zone' companion you want beside you if the night becomes … interesting!

Work Cited

1. Miller, Ben. Irish Swordsmanship Fencing and Duelling in Eighteenth Century Ireland. (New York NY, Hudson Society Press, 2018.) 220

2. Ibid. 26.

3. Ibid. 220.

4. Ibid. 220.

5. Ibid. 242.