♪"Stop, Hammer time!"♫ (Apologies to MC Hammer.)

What is a cultural ‘artistic’ reference in our time, was an invitation to ‘bring it’ in medieval times.

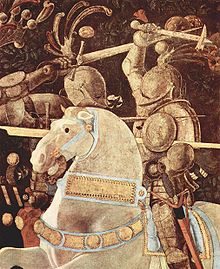

For nearly two centuries, the warhammer was a weapon of choice for mounted medieval armoured combat. However, there seems to be a distinct lack of (recorded) knowledge of the fighting techniques that were used with the weapon.

For nearly two centuries, the warhammer was a weapon of choice for mounted medieval armoured combat. However, there seems to be a distinct lack of (recorded) knowledge of the fighting techniques that were used with the weapon.

In Warhammer, the Forgotten Weapon, Roth (if that is in fact his real pseudonym) intends to provide us with a ‘meditation’ on the warhammer, to describe its technical development, and to place the weapon in its historical context as a weapon for the mounted man-at-arms. While his qualifications to write this guide are a bit difficult to pin down, it’s obvious very early on into the book that this author has an expertise with both the theory and practicality of fencing with a variety of weapons. Furthermore, Roth's military background comes to the fore as he begins to write about where the warhammer fits in with developments in armour and combat technique.

The organization of Warhammer is of the usual style; Roth starts with a short history of ‘blunt weapons’, such as clubs and maces, passes into hammers as depicted in myth (any guesses?) and then gets into the nitty-gritty of discussing what a warhammer is for, why it is designed so, and how was it used. He then lists localised developments of the weapon that occurred in Germany, the Ukraine, Poland and even among 17th century Cossacks.

This is not a ‘Fechtbuch’, although "Chapter 4: Fencing with Warhammers" considers in detail all those elements of time, ‘beats’, distance, cuts versus thrusts, and proper position that any Master would need to consider before putting quill to paper to guide the use of any weapon. Roth does intermittently discuss ‘dis-similar combat’ as he describes the potential advantages of the warhammer over contemporary arms in use on horseback – but it would have been most educational to get his interpretation on how warhammers were used against each other.

My favourite bits are his descriptions of the ‘arms race’ between attack and defence – the adaptions in the hammer’s ‘crushing face’, its penetrating beak and handle length that we’re constantly morphing as users react to developments in armour coverage (including the lack thereof), or even regional preferences.

We also get short chapters on ‘combination warhammers’ – those exotic weapons built with the hopeful intent of providing two weapons in one haft (though what they invariably got was one ‘second-rate’ weapon). Warhammer sword canes and pistol combinations feature predominantly, as do hammers with axes instead of ‘beaks’. I was both amused and intrigued by the photograph of the German 1593 combination warhammer/polearm; which looks to me to be the first functional Swiss army knife built for renaissance infantry (p.83).

Production-wise, the book is supported by workable black and white photography, but sometimes fine detail is lost in muddy backgrounds. The text, while not always elegant is very technically descriptive and logical, and effectively supports the author’s intent. The purchase cost of this small book might be of modest concern, but if you consider that you’re getting a unique, original work on a weapon that gets very little in-depth discussion in other history or swordplay books, it will be worth it.

To finish, Roth issues a clarion call that any martial artist should heed regardless of their chosen discipline or related weapon: we need to challenge our hazy understandings and incomplete comprehensions of some past weapons with more detailed study of the written, artistic and real examples of their use that still remain – and have yet to be properly inventoried and released to the martial arts public.