I love taking workshops with experts who have a lot of experience like Marco Quarta. The value of their coaching is immense, but I get even more from their explanations, their unique perspectives and the insights about why we choose certain movements. Maestro Quarta is an expert in Italian martial arts, especially traditional and modern stick fighting.

In Marco’s 4-hour workshop last Sunday, which turned into a 5+ hour exploration as we all lost track of time, we covered topics that were very relevant to Bartitsu, including striking and grappling, knife fighting and short stick combat.

A Theory of Strike Targets

In self-defense, it is important to try to stop your assailant as soon as possible. How does one prevent an attacker from continuing their attack?

One strategy is to cause sufficient damage to anatomical structures that are necessary for attack and pursuit when you choose to escape. In Bartitsu, we strike with the stick and low kicks to the knee so that the opponent can’t stand or chase, and aim punches for the mark and the throat to affect breathing.

In addition to these same strategies, Marco adds that strikes that cause shock and trauma can also be effective. For example, a bloody nose is not going to stop a fighter. In a high stress situation he is already breathing through his mouth, so the blood clogging the nose is barely noticed, and he has probably experienced a benign bloody nose previously. He knows without much analysis that it is not a catastrophic injury.

When striking with hand or stick for self-defense, Marco suggests that the places that cause an attacker to pause or break off his pursuit can are mapped by the psychological homunculus.

Mapping

Before I explain the homunculus, take a look at this world map:

This shows the population in the year 1900, with country sizes shown in proportion to their population instead of their geographical area. It’s a way of understanding data in a way that denotes the importance of the metric we’re concerned with, in this case, population. Okay, now let’s look at another map.

The Somatosensory Homunculus

A homunculus is general term in philosophy for a “little man” to explain certain phenomena. Often, the homunculus is imagined to live inside you. One may explain vision by noting that light from the outside world forms an image on the retinas in the eyes and something (or someone) in the brain looks at these images as if they are images on a movie screen. The question arises as to the nature of this internal viewer. The assumption here is that there is a ‘little man’ or ‘homunculus’ inside the brain 'looking at' the movie. (Thanks, Wikipedia.)

The homunculus argument is usually a fallacy similar to begging the question or circular reasoning. The most recent episode of the excellent You Are Not So Smart Podcast explains this: https://youarenotsosmart.com/2016/04/22/yanss-074-begging-the-question/

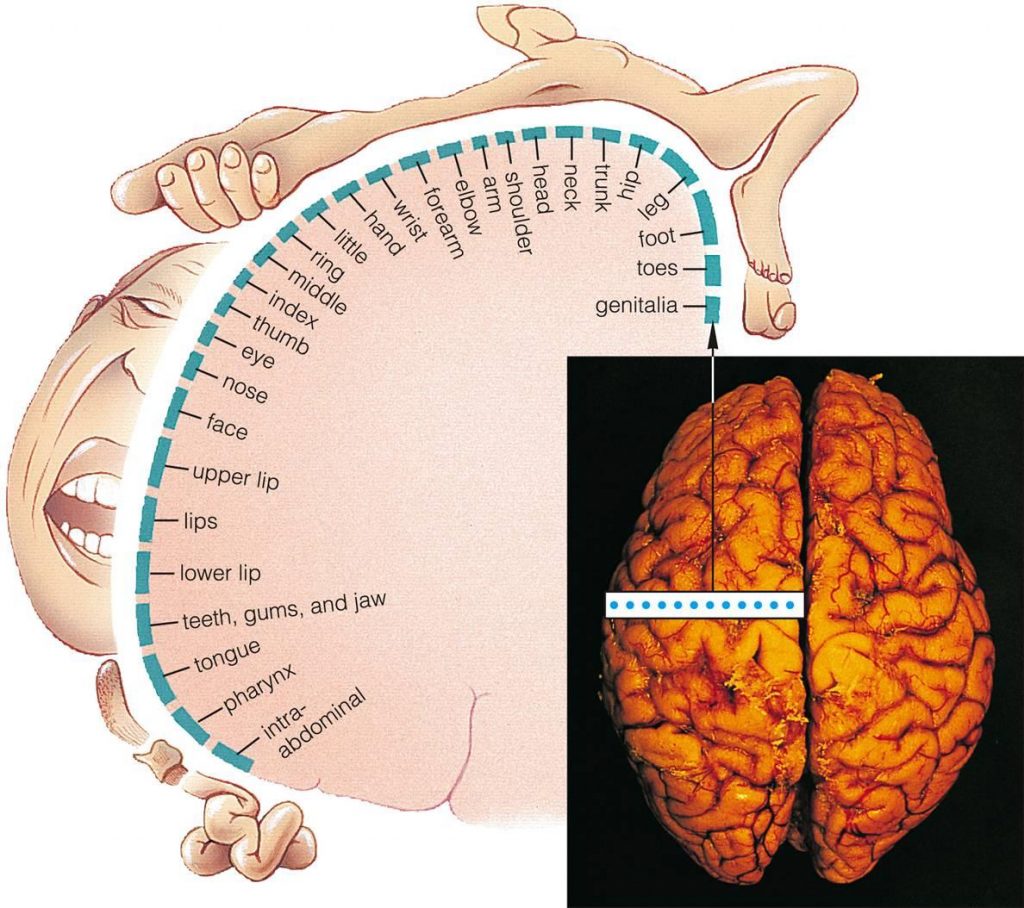

However, there is a different kind of homunculus in your brain: a visualization of the number of neurons that correspond of different parts of your body. There’s one motor-neuron homunculus for the parts of your brain that control your motions, and another one for the parts of your brain that feel sensations. We call the second one the somatosensory homunculus, and it looks like this:

Let me emphasize that this is just a way to picture how much brain matter is activated by feeling the different parts of your body. Like the population map, it’s a visualization of the data we’re interested in. It is also not a distorted body image, we all know that we don’t think of ourselves as having such extreme proportions.

Let’s look at those proportions. All of following zones are almost equal:

- The foot compared the rest of the leg

- The middle finger compared the entire forearm

- The upper lip compared to the elbow, shoulder and neck combined.

Marco’s theory is that damaging parts that have larger brain representations cause more subjective trauma. He recommends against striking the trunk, and to instead prioritize:

- Lips and mouth

- Hand and wrist

I loved this theory when I heard it in class. I thought it was a brilliant connection between neuroanatomy and martial arts, and I'm a fan of a scientific approach to combat. Its simplicity also appealed to me, because I could immediately visualize what he was talking about. I know this may be new to some of my readers and to other students at the workshop, but once you see the homunculus, those strike targets become obvious.

Thinking back to those times when I've split my lip badly, I recall how deformed my face felt. When my tongue is burnt, it feels twice its normal size. So the subjective feeling of trauma when those parts of the body are hurt rings true for me.

Stick fighting and knife fighting will often target the hands, and our high guards in Bartitsu reflect our concern about preventing that. However, I’m not convinced it’s the traumatic psychological effect, but rather the practical effect of not being able to grasp or punch effectively which stops the attacker.

The more I looked at the homunculus and tried to link it with other information about shock and violence prevention, the more dubious I became. It's a neat theory, but I'm not going to endorse it.

I personally still think that striking to cause physical damage to vulnerable parts that are critical for continued attack is the best approach. In the homunculus theory, the eye is about equal to the nose or the toes, but I believe an eye gouge would be both more traumatic and a better physical deterrent than breaking a toe.

It’s always a good exercise to examine your assumptions and analyze what you’re offered, whether that be in the realm of martial arts or any claim. I hope my students always take a critical eye to their own practice and my advice as well.

For more on the homunculus, here's the Crash Course Psychology episode about it: