My blood began to boil, my temper I was losing.

And poor old Erin's Isle, they all began abusing.

"Hurrah! my boys," says I, my shillelagh I let fly.

Some Galway boys were by, they saw I was a hobble in;

Then with a loud "hurrah !" they joined me in the fray.

-- The Rocky Road to Dublin.

The Irish are known as fighters, even to the point of characterization (The Notre Dame fightin’ Irish come to mind, which we’ll look at later) but when we actually look at the evidence this tends to hold true as well. Whether we look at Conor McGregor -- who despite his recent defeat has put Ireland on the MMA map -- or the proportion of Ireland’s Olympic medals that have come from boxing (about 60%), there is a clear trend that supports this stereotype. This piece is going to be a whistle-stop tour of some of the Irish fighting arts of recent history and what they have contributed to modern martial arts.

It is extraordinary what a lot of knocking about a sturdy Irishman can put up with, and what whacks he can receive on the head without any apparent damage. One cannot help thinking that the Celtic skull must be thicker than the Saxon.

-- R.G. Allanson-Winn and C. Phillips-Wolley. Broadsword and Singlestick.

Unfortunately, there are no authentic historical texts that specifically explore the Irish arts themselves (arts that we have references to, but no actual written sources for), and many sources that reference specific Irish arts are of questionable provenance. For example, the text from which the above quote derives references the use of the shillelagh, the quintessentially Irish weapon. However, this seems to come from the author's experience of seeing shillelagh exhibitions at travelling fairs (and possibly studying with the fighters) as opposed to any exposure to a distinct martial tradition, and is much more a commentary than any sort of instruction in the art. This means that unlike many other countries in Europe, much of Ireland’s martial history is likely lost forever.

Collar-and-Elbow (Wrestling)

Collar-and-elbow is a form of Irish wrestling that we can trace back to the 17th century, but it likely existed before this. It shares a lot with other forms of peasant fighting from the period and is distinct for its start position, where the competitors literally grip each other’s shirt collar and elbow. This position is still present in modern wrestling today in the form of the collar-and-elbow tie. Participants and practitioners were known as "scufflers" or "trippers".

Collar-and-elbow wrestling started from its namesake position, which meant that it was difficult to overcome your opponent using a sudden rush. Instead, it relied on a variety of tripping throws (known as "mares", specifically, when the feet of the opponent ended up higher than their head), as well as shin kicking and ground fighting techniques. The inclusion of ground fighting can be linked to the win conditions of a collar-and-elbow match, which required the successful pinning of an opponent. These specific win conditions differentiate Irish wrestling from many other styles of folk wrestling from nearby regions (like Cornish and Scottish Backhold wrestling) which relied on falls to determine the winner and lacked a significant amount of ground fighting game for this reason.

Although we have references to coraiocht (the Irish term for wrestling) prior to this in myths and legends, it is hard to distinguish particular nuances of style to separate it from folk wrestling styles the world over, until it becomes the distinct collar-and-elbow tradition. One of the most significant factors in solidifying this as a wrestling style is the mass emigration of the Irish to North America during the great famine, where suddenly styles of fighting that were purely utilitarian and practical became cultural hallmarks of the homeland and the family to which they belonged. In this environment, schools of the art were established and many famous figures (including George Washington) studied the art. The biggest legacy of collar-and-elbow today was its contribution to catch-as-catch-can wrestling, or "no holds barred" wrestling, which forms the basis of much of the grappling used in MMA.

Bataireacht (Stick Fighting)

A choice selection of fencing-sticks used to be placed on a stand in the street opposite to this establishment. A grown male person handling one of these sticks through curiosity would be asked by a pupil of the school: “Are you able to use that stick?" and the answer being in the affirmative, battle was at once joined. Thus did the school advertise itself....

--Lyons, P. "Stick-Fencing." Béaloideas. (1943.)

The Irish blackthorn stick, or shillelagh, is one of the only Irish traditions of weaponry that has survived to the modern day. This has happened in two distinct ways, the first being through traditions of direct transmission within families, and the other being through the existence of several manuals that reference the use of the stick and teach techniques to go with it. As discussed above, the historic texts do not necessarily represent an accurate or complete view of the system. Several HEMA groups have made efforts to reconstruct the arts in recent years, which has greatly increased the visibility of a once near-extinct art.

Another important point to make when discussing Irish stick fighting is the sheer volume of what those words could cover. Through historical references we know of many different -- and now extinct -- varieties of Irish stick fighting that may have had little relationship to each other. These include styles using a single stick in one hand, a stick in both hands, and two sticks. The fighting art was primarily one of self defense, and the settling of disputes, often in large-scale brawls called faction fights, which could take place between hundreds of people representing different groups.

In terms of the family lineage, there are several schools claiming to be authentic and to have a direct, unbroken line into history. The most prominent and well-known of these is the "Rince an Bhata Uisce Bheatha", or the "dance of the whiskey stick" of the Doyle family of Newfoundland.

The Doyle family’s method of stick fighting came to its current lineage holder, Glen Doyle, through his father, who claimed that the system was brought to North America by his ancestors from Ireland and kept alive in the family ever since. The style itself requires two hands on the stick, and according to family legend, the method was derived from a knowledge of pugilism from the time. This certainly seems plausible given the similarity the fundamental strikes share with boxing.

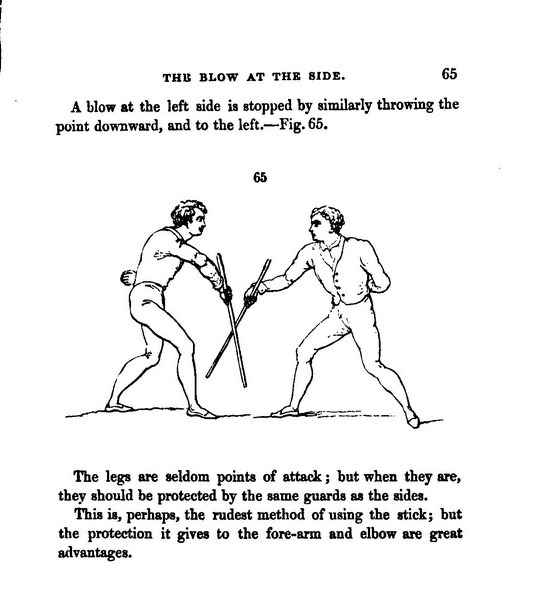

Another tradition claiming to have a direct lineage is Antrim Bata, a primarily one handed style from Northern Ireland that traces its origins to an Antrim based fighter named Tickety Boo. This style was kept private until the year 2000, when it was taught to outsiders for the first time. Antrim Bata is closest to what we see in the few texts that claim to teach the shillelagh. For instance, it uses what is called the Irish grip, where the stick is held single handed about two thirds of the way from the bottom, with the thumb on the back of the stick. Furthermore, the lower third is often used for parrying, which is a very unique facet of Irish stickfighting not found in other styles that draw much of their basis from different styles of swordfighting.

Dornalaiocht (Boxing)

As already mentioned, boxing has a special place in Irish sport, and has for a long time. The Irish influence on boxing was not an art unto itself, but a successful series of bare knuckle fighters within the varied discipline that is simply labelled boxing, or prize-fighting. Probably the most iconic and recognisable image of this is the mascot of the Notre Dame Fightin’ Irish, which depicts a leprechaun posed in a fighting (sorry, fightin’) stance.

Like other traditions we have discussed, this boxing style largely flourished among immigrant communities in North America. Irish boxers in bare knuckle boxing had a reputation that was well deserved. An important thing to note about the sport -- which in its varied history actually at times included grappling and headbutting (among other things) -- is that before transitioning to modern sport boxing, fights were often feats of endurance much more than we would normally associate with combat sports. Some matches lasted 80 plus rounds, with the longest recorded being over six hours long.

Probably one of the most influential Irish boxers of all time was John L. Sullivan, an Irish-American boxer who was the last champion under the London Prize Ring Rules (which initially governed boxing), thus making him one of the last bare knuckle boxing champions as the sport gave way to sparring with gloves (under the newly introduced Marquess of Queensberry rules). Sullivan served to bridge between the two as he fought under both rule sets -- gloved and bare knuckle -- and won titles in each. One of the most impressive feats was his match against Charley Mitchell, a British fighter, fought in France in the driving rain. The fight was declared a draw after two hours, at which point both fighters were reported to be covered in blood and unable to lift their arms. The most interesting element of this fight was the fact that Mitchell was arrested afterwards, and Sullivan had to be smuggled into England to avoid charges as the sport was illegal in France at the time.

There is one important difference between bare knuckle boxing and the other fighting arts discussed, and that is that bare knuckle boxing is still practiced in Ireland, though underground and illegally, in Ireland’s Traveller community (similar competitions exist among English Traveller communities). For those of you that don’t know, the Travellers are a group of indigenous Irish itinerants, also known as Pavees. Within Traveller culture a number of traditions have continued that have died out in conventional society, and one of those is bare knuckle boxing.

Within Traveller communities these competitions are generally informal, based along family lines and used to settle (or in many ways, often further) disputes between families. This martial family dynamic is in many ways similar to the original shillelagh faction fights, which were family vs. family, or village vs. village, and often both meant to resolve (and in turn tended to create new) grudges.

Conclusion

Of the Irish fighting arts there are stark similarities between each discipline (wrestling, stick fighting, boxing) that set them apart from many of the traditions we are used to in Historical European Martial Arts. They are generally familial, passed down from generation to generation through direct transmission and are the arts of peasants and the working class. They have survived not through the patronage of wealthy noblemen, or the theoretical writings of dedicated participants and masters, but through careful preservation -- often behind closed doors -- of arts that were inherently practical, but also deeply tied to a cultural memory of the practitioners' homeland. Irish martial arts are artifacts of a time and place in Irish history, and like all aspects of Irish history, are intrinsically tied to a narrative of oppression and emigration.