How do you transmit the precise movements of a performance to future performers? As a fight choreographer, I need to plan action scenes and teach them to actors. I need a method of recording human movement.

Today, we’ll explore the options of how to write the movements in your choreography so you can best communicate them or aid your recall. Fight Directors Canada has a standard way, but we’ll also explore the ways dancers have done it, and what technology can help us.

Why Record?

First, a quick note about reproducing choreography: All combat is choreographed for the safety of the performers and to tell the best story possible. In some events, such as professional wrestling, many of the sequences are improvised within a story structure that is agreed upon beforehand. However, in film and on stage, fight scenes are planned to the move.

The choreography needs to be recorded because performers do not have perfect memory. The fight director would like the actors to review their movements at home and practice with their partner, and having a document to refresh their memory is critical. An actor has a script to learn their lines because we expect them to memorize them and not just improvise. Especially when safety is a factor, all performers need to reproduce the fight the same way every time.

Narrative Writing

The first method we’ll look at is used in descriptions of movement in every medium: Write it in full sentences as if telling a story. One recent example I saw was this blog post about a fight in the TV series True Detective: Telling the Story Blow By Blow: True Detective

The blogger doesn’t cite a source for the script, so it could have been a fan-made reconstruction of the scene after watching the episode. That actually doesn’t make a difference for our purposes. Whether the original screenwriter put that detail into the fight, or if a diligent fan transcribed the dialogue and the action, we nevertheless have a narrative description of the fight.

One of my favourite examples of narrative fight writing is from Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Christopher Hampton:

Dawn on a misty December morning in the Bois de Vincennes.

On one side of the stage, VALMONT; on the other, DANCENY. VALMONT is making his selection from a case of epees. He weighs now one then another in his hand. DANCENY, meanwhile waits impatiently, in shirt sleeves, epee in hand, shifting from one foot to the other. Finally, as VALMONT seems to be on the point of making his decision, DANCENY can restrain himself no longer.

DANCENY. I know it was easy for you to make a fool of me when I trusted you, but out here I think you’ll find there’s little room for trickery!

VALMONT. I recommend you conserve your energy for the business at hand. (VALMONT makes his final choice of epee and lays it on the ground…off with his coat and on with a black glove. Then, VALMONT and DANCENY approach one another and take up an en-garde position. The duel begins, fierce and determined, VALMONT’s skill against DANCENY’s aggression. For some time, they are evenly matched, with VALMONT, if anything, looking the more dangerous. Then DANCENY succeeds, more by luck than good judgment, in wounding VALMONT in whichever is not his sword arm. The duellists resume an en-garde position and begin again. This time, it’s DANCENY who looks to have the initiative. For some reason, connected or not with his wound, VALMONT seems to have lost heart, or even interest, and at one point, with the deflection of a too-committed attack by DANCENY seems to leave him wide open, VALMONT fails to take advantage of what seems to be a golden opportunity. Eventually, in some piece of inattention very close to carelessness on VALMONT’s part, which allows DANCENY through his guard with a thrust which enters VALMONT’s body somewhere just below his heart. There’s a moment of mutual shock, and then DANCENY withdraws his sword and VALMONT staggers a few steps towards him, before subsiding with a slight gasp to the ground.) I’m cold.

As you can see from these examples, authors can convey a lot of information about the tone of the fight, the necessary moments that the author is prescribing, and should give you the foundation for your choreography.

It’s a lot more to work with compared to Shakespeare’s “They Fight.”

But we’re not merely talking about how playwrights and screenwriters tell us about fights. You can use the same technique to write your choreography whether you’re a fight choreographer, or an actor who wants to make note of their own acting moments in the fight. Not only can you capture the moves, you can also include any details about the costume, the movement through space or around objects, and the emotional changes.

Bruce Lee wrote in long hand. His daughter reads from his notes on Game of Death: “As Bruce launches a side kick, Kareem outreaches him with his front snap punch while still sitting. Bruce falls flat.” That is directly from the document Lee used while filming.

Narrative Writing:

Advantages: Detail of gesture, spacial orientation, emotional life and motivation, whatever is important

Disadvantages: Information is not compact or easy to follow. You have to read through a few sentences to figure out your next move.

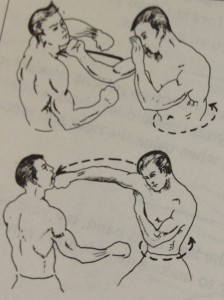

Sketching

Besides narrative writing, Bruce Lee also practiced pencil sketching, and used it in some of his choreography. He could do detailed studies in which he drew boxers throwing the ideal punches, but the volume of moments within a film fight necessitated a faster style.

Professional ballet choreographers often use a sketch or stick-figure drawing for recording human movement. You can see the ballet choreographer designing the dance in this screen cap from the trailer for the new film Ballet 422:

After all, using words to convey the position and motion of the body is often complicated and prone to misinterpretation. I know this first-hand in writing about both stage combat and Bartitsu.

It doesn't take an expert pencil artist to record choreography in this way. Stick figures can suffice. However, some practice is necessary just to get proportions correct. Certainly, if you want to show every move of a fight, you'll have to develop speed-drawing without losing clarity.

Sketching

Advantages: Visual learners and film directors who want to plan storyboards

Disadvantages: Impossible without diligent practice at drawing, unclear sword crossing, not amenable to showing intent or emotion

Narrative Plan

Whatever your skill level at drawing, everyone has trouble depicting sword interactions in a still image. When it comes to swordplay and other martial arts, we already have a vocabulary so that we can talk about how movements work. We’d like to incorporate that vocabulary, but we want a clearer way of compressing the information from the narrative writing style.

A simple style to adopt when writing your narrative is to take each distinct move (an action from one actor and the reaction from their partner), and always write the operator first. In this way, we don’t get lost in a jumble of description, and we can easily find move numbers to start at.

Here’s an example if you’re transcribing from a film like The Princess Bride:

0: Wesley and Inigo both left-handed, en garde with tips lowered

1: I. cut L arm, W. parry 3

2: I. cut L hip, W. parry 2

3: I. slash diag down, W. evade left

4: Circle each other until W. back is to stairs

5: I. thrust R arm, W. parry 4

6: W. thrust R arm, I. parry 4

7: W. slash diag down, I. evade left

Narrative Plan

Advantages: Clear to read, fast to write

Disadvantages: With attacker first, a performer still has to read a lot to find their next move. Following the flow of one character’s intentions is lost.

Tabular Plan

If we take that narrative plan and put it into a table, we’ve got a tabular plan. We use the same move numbers, but now we have a column for each character. In order to show the direction of attack, we add a column between the two characters for an arrow of intention.

This is the most popular format in Fight Directors Canada. If you get stuck trying to remember a sequence, it is easy to find your place and pick up your rehearsal from there, even if you don’t remember the number.

Here’s what the same fight might look like:

| Move | Inigo | vs | Wesley | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Left-handed low guard | Left-handed low guard | ||

| 1 | Cut L Arm | → | Parry 3 | |

| 2 | Cut L Hip | → | Parry 2 | |

| 3 | Slash diag down | → | Evade Left | |

| 4 | Circle clockwise | Circle clockwise | W. back to stairs | |

| 5 | Thrust R Arm | → | Parry 4 | |

| 6 | Parry 4 | ← | Thrust R Arm | |

| 7 | Evade Left | ← | Slash diag down |

Tabular Plan

Advantages: Clear to read, fast to write if you’ve got a blank table pre-printed. Standard in FDC.

Disadvantages: To fit into the boxes, much information may be compressed or abbreviated beyond comprehension. Movement around the performance space is difficult to incorporate.

Dance Notation: Labanotation and Sutton

The concept of dance notation, like fight notation, is to record the movements of the body without needing to reference a specific historical style. It may be easy for those doing classical ballet to describe in words (position two, plié, jetée, etc), but modern dance, different cultural dances for which the dancer has no vocabulary, or variations from the norm for new expression cannot be described so easily.

A recent article in the Paris Review gives some overview of the history of this process: How to Write a Dance

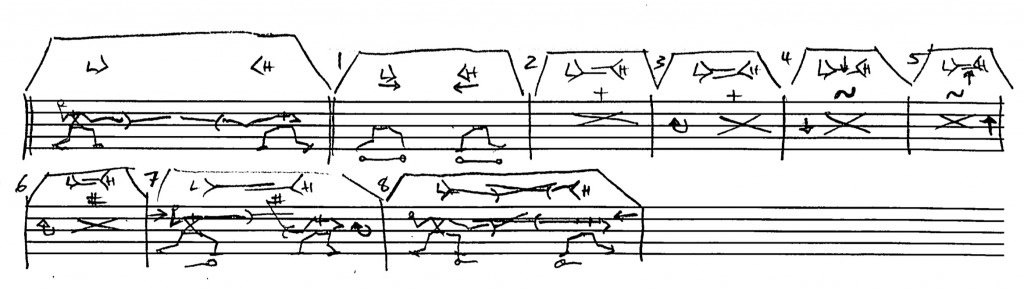

One of the most recognized forms of “sténochoréographie” is known as Labanotation. Rudolf Laban studied the ways the human body can move, and created an abstract notation to isolate the degree of flexion of each joint and the quality of motion when changing position. It looks like this:

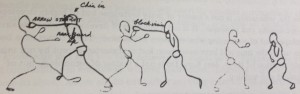

It is utterly incomprehensible without a semester of study. Other alternatives were devised, such as Sutton dance notation. It also uses a musical staff, but instead uses stick figures with standard dimensions to visually show the performer. I experimented using it for fight choreography.

Inside the lines, two stick figures for two fighters. In some frames their upper bodies are missing because I only show the necessary change from the previous frame. Above the lines, an overhead view of their position on stage and the relationship between the swords.

I have to admit that if I wanted to use this, even for my own reference, I’d have to get a better method of showing parries. I find it easier to draw freehand than to fit my stick-figures into the music staff. However, you may embrace the idea and run with it. I know of nobody who uses either of these dance notations for stage combat, so if you find a great method, you can be a pioneer.

Dance Notation

Advantages: Specificity and precision of position.

Disadvantages: Steep learning curve for writing and reading. Interaction between performers may be misunderstood.

Video and Slideshow

In 2015, digital video cameras are in every cellphone. Why not record your choreography that way? The reason this article is not called “Writing Choreography” is because the plan for a fight can easily be recorded in other ways.

If you are choreographing a fight with an assistant, you will want to dress in different colours so that the viewer can easily tell you apart. Then, you can teach it to your performers who will see and try to imitate your perfect form. You can also show this “first draft” of your choreography to the director to see if they like the flow of the fight before the actors get confused with changes to their fight mid-rehearsal.

In a film production, you should consider your camera angles for each sequence as if directing the movie yourself. Do it as a pre-viz to help the director and the actors understand why certain angles work.

It also may be practical to record the actors when they can perform a phrase well. That way, they don’t have to remember that they’re copying the “guy in red”, they can simply see themselves doing it. The problem with this method is that they may require a lot of corrections to their posture and targets and overall movement, so you don’t want to record them performing a sub-standard fight for reference.

A full-speed video may be difficult to follow, and your performers may have to pause and rewind again and again to understand a move. Every aspiring martial artist has done this with their favourite fight scene to copy their idols, and we know how annoying it is. If you have the editing software and a little time to learn to use it well, you can slow down your footage in complicated sequences or incorporate an instant replay. You can also freeze-frame to annotate with written notes to explain anything that is unclear in the video.

If you want to go one step further, go through your video move by move and export a still image of each moment. Then, you can assemble those frames into a slideshow to accompany your written choreography using one of the other forms we discussed earlier.

Video

Advantages: The most precise description of where every body part moves, and movement within the space (or the film’s frame) is clear.

Disadvantages: Without slow-motion or freeze-frames with descriptions built in, the performer will have to rewind over and over. Without annotations for every move, the actor doesn’t learn enough vocabulary to talk about the fight or give feedback.

Slideshow

Advantages: A still image of every move is very accurate, but has advantage over a video because the performer can flip to a precise part of the fight without loading a video app and scrubbing along a timeline.

Disadvantages: It takes time and effort to step through the video to capture the stills then reassemble them and annotate.

Which is Best?

Use your favourite. I always recommend recording video, even if you’re not going to use it for your primary documentation. However, if you choose to use video, don’t forget that writing things down can be a great aid to recall.

I came by these various methods through research and experimentation with my own choreography on different shows. Do your own experiments to discover what you connect with most strongly. Remember to consider your reader: are you sure you'll only use it for personal reference, or will actors also have to understand your notes? Different people learn in different ways, so don't assume the visual is better than using words. Some combination is usually the best, which is why I prefer using the slideshow method for professional shows with complicated fights.

Narratives Come To Life

On 23 March, the Academie Duello Performance Team will illustrate fights from local writers’ works. Their narration of fight scenes is used as a template for our fight choreography, except in the case of our graphic artist who gives us frames like the slideshow technique. On Monday, March 23, join us at the Central Branch of the Vancouver Public Library at 7pm for dramatic readings with full sword fights!