The core martial system of Academie Duello traces its origins to the violent streets, dangerous battlefields, and duelling grounds of Northern Italy in the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

The core martial system of Academie Duello traces its origins to the violent streets, dangerous battlefields, and duelling grounds of Northern Italy in the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Academie Duello's system focuses on weapons and teachings from a period of history which spans 300 hundred years, from 1400 to 1700, drawing upon a martial tradition that begins with the Longsword and Wrestling of Fiore dei Liberi in the 1400s and concludes with the Italian Rapier and its masters such as Salvator Fabris and Ridolfo Capo Ferro in the 1600s.

Though our system spans a large historical period it is integrated in such a way that each discipline serves to teach core principles which relate to the system as a whole. The point-oriented rapier emphasizes the principles of geometry, timing, and distance; the longsword emphasizes flow, 360-degree movement, and the blend of wrestling and swordwork; the sword and shield fuse together cut and thrust and hone the deceptive and fluid aspects of the art; unarmed and dagger skills focus on core body mechanics, contact perception, and the skills required to survive a close engagement.

Beyond our core system, Academie Duello also hosts Archery and Mounted Combat programs.

When you come into Academie Duello you’ll find that much of the language we use is Italian. Italy was a hotbed of martial practice throughout the middle ages and renaissance and has some of the most effective and well documented martial systems. The Academie Duello system incorporates the teachings and core principles of Italian Swordsmanship with an emphasis on 4 key elements:

When you come into Academie Duello you’ll find that much of the language we use is Italian. Italy was a hotbed of martial practice throughout the middle ages and renaissance and has some of the most effective and well documented martial systems. The Academie Duello system incorporates the teachings and core principles of Italian Swordsmanship with an emphasis on 4 key elements:

- Tempo – Awareness, and control of the key moments to control and strike the opponent.

- Geometry – The optimal positions to place your weapon or body to constrain your opponent mechanically and strategically.

- Distance – The right technique in the right place and the relationship between distance and time.

- Body Mechanics – Strong mechanical alignment of your body and the ground to create power and precision with the least amount of exertion.

The weapons we teach include:

- Rapier,

- Longsword,

- Sidesword,

- Polearms (like the poleaxe, spear, and quarterstaff).

Complimentary weapons are also employed including:

- Dagger,

- Two swords,

- Various shields (buckler, rotella, kite, round),

- Cloak

Most Academie Duello programs follow a ranking system. Ranks allow a student to set goals, understand their progress, and learn new skills in a structured and efficient fashion.

Most Academie Duello programs follow a ranking system. Ranks allow a student to set goals, understand their progress, and learn new skills in a structured and efficient fashion.

Like many Eastern martial arts schools, we have a series of ranks represented by different colours and traditional names. Progression through all five levels of our ranking system is accomplished via private assessments with instructors and public examination for higher levels, with students earning a coloured cord for each rank achieved. Attaining the rank of Master is a 7 - 15 year journey, depending on the intensity of your studies. However, we foster a highly supportive environment and students are encouraged to move at their own pace.

There are two points of entry for our ranking system: Beginner Longsword (which focuses on the medieval longsword), and Beginner Rapier (which focuses on the renaissance rapier). In Canada, Academie Duello is the only authentic Italian Renaissance Swordsmanship academy, and students must complete one or both of these courses to achieve the rank of Apprentice, the prerequisite for higher-level studying in the school.

Academie Duello employs the following 5 ranks:

Apprentice (Green Cord). Weapons: Rapier or longsword and unarmed skills. Principles: Familiar with body mechanics, distance, and control. Achieving the apprentice level comes with the completion of the test at the end of one of our two primary beginner programs.

Scholar (Blue Cord). Weapons: Rapier and rapier & dagger, or, longsword and half-swording, along with, sidesword, sidesword and shield, and unarmed. Principles: Angle, line, cutting mechanics, timing and proportion. On average, students progress from Apprentice to Scholar in 6 months to 2 years of training.

Free Scholar (Red Cord). Weapons: Rapier and secondaries, sidesword and secondaries, longsword, quarterstaff, knife, and unarmed. Principles: Timing, tempo, power generation, strategy, and tactics. On average, students progress from Scholar to Free Scholar in 1 to 3 years of training.

Provost (Silver Cord). Weapons: Rapier, sidesword, longsword, pole weapons, knife, and unarmed. Principles: Centres and tempo. Provosts are expected to be highly proficient in the system of arms, able to diversely apply its principles, and be able to challenge its implementation to build and grow the art. A Provost completes a series of trials in the areas of research, teaching, and martial prowess to achieve their master level.

Master (Gold Cord). Masterful in the application of the system of arms. Able to proficiently apply their skills across all disciplines armed and unarmed. Able to pass the art on to others at a high level and to innovate and grow its practice at Academie Duello and for the Italian Martial Arts community as a whole.

Mounted Combat

Academie Duello’s Mounted Combat Program follows a different ranking system, with students earning different coloured spurs to mark their progress through each new level of proficiency. The ranks of the program are:

Green Spur: Horsemanship and Riding Level 1 (or Equine Canada Level 1, or Canadian Pony Club Level D), sword proficiency from the ground.

Blue Spur: Horsemanship and Riding Level 3; sword, spear and wrestling proficiency from the ground; sword and grappling proficiency from the falsemount; mounted games at a trot.

Red Spur: Horsemanship and Riding Level 6; sword, spear, sword & shield and wrestling proficiency from the ground; sword, spear, sword & shield and wrestling proficiency from the falsemount and mounted; mounted games at the canter.

Silver Spur: Horsemanship and Riding Level 8; mounted combat with safety swords; mounted games with live swords; mounted archery.

Gold Spur: Horsemanship and Riding Level 10; mounted falconry.

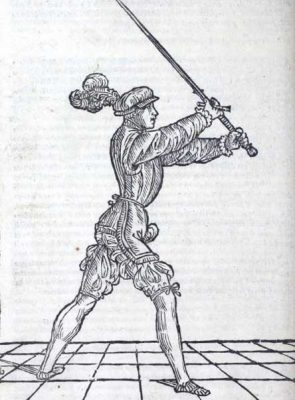

The rapier is a long, thin-bladed sword particularly suited to the thrust. It was first popularized in the late 1500s and early 1600s as the primary weapon of the duel throughout Europe. An intricate and sophisticated weapon, the Italian rapier is ideal for teaching the fundamental swordplay principles of distance, timing, blade interaction, and combative strategy.

The rapier is a long, thin-bladed sword particularly suited to the thrust. It was first popularized in the late 1500s and early 1600s as the primary weapon of the duel throughout Europe. An intricate and sophisticated weapon, the Italian rapier is ideal for teaching the fundamental swordplay principles of distance, timing, blade interaction, and combative strategy.

Though the modern fencing épée is derived from the rapier, the sporting form seen now in the Olympics is quite distinct from the martial dueling techniques taught at Academie Duello. The rapier is a much longer and heavier weapon suited to both the cut and thrust. The system of fencing employed includes movement in the round (circling an opponent), use of a second hand or 'offhand' to deflect and seize an opponent's rapier, and the use of various complementary tools called secondaries, such as bucklers and daggers.

Anatomy of the Rapier

The rapier is a famous Italian sword that is a long and slender weapon oriented to thrusting. It reaches typically from 41" to 50" in total length, while the blade itself is between 36" and 45" long. Typical rapiers weigh between 2 and 4.5 lbs overall. The balance point is typically 2" to 4" from the guard along the blade.

The rapier is a famous Italian sword that is a long and slender weapon oriented to thrusting. It reaches typically from 41" to 50" in total length, while the blade itself is between 36" and 45" long. Typical rapiers weigh between 2 and 4.5 lbs overall. The balance point is typically 2" to 4" from the guard along the blade.

Most rapiers also have a complex hilt that provides protection for the wielding hand, either in the form of a swept hilt (bands of metal stemming from the crossguard, 'sweeping' around the grip) or a cup hilt (a cup-like metal plate fixed in front of the crossguard, with one or more sweeping bands as well).

The Nature of the Rapier

Duellists seek positions where they have optimal leverage and cover from an opponent's rapier. They use rapid and delicate movements, sliding along, turning and occasionally clearing an opponent’s weapon. The threat of an opponent’s rapier point is constant, pointed always at its intended target.

Duellists seek positions where they have optimal leverage and cover from an opponent's rapier. They use rapid and delicate movements, sliding along, turning and occasionally clearing an opponent’s weapon. The threat of an opponent’s rapier point is constant, pointed always at its intended target.

At Academie Duello, the core strategy for rapier in the Italian system is to constrain an opponent’s options through conscientious positioning of sword and body. The posture for rapier involves standing in profile, leaning forward and back into the guards, proper sword and body alignment for optimal strength and striking angles, and the use of the lunge as a primary striking movement. The line of the entire body moves the rapier; the thrust comes from the lunge, not a movement of the arm.

Sword and movement place a duellist in such a position that renders an opponent unable to attack from their own position, causing them to move to a more advantageous place. During this movement, a duellist creates an opportunity to further improve his or her own position or strike.

History of the Rapier

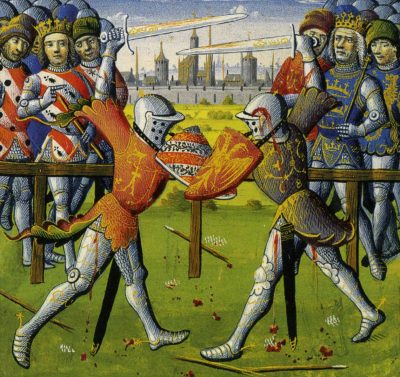

Late medieval and renaissance cities were rapidly growing, crowded places filled with people from all walks of life. Violence erupted often enough and many people carried weapons for protection. By the middle of the sixteenth century, a new and socially acceptable practice had emerged to settle civilian disputes with weapons—the duel—with specialized weapons and fighting systems to complement it. Up this point, the swords most often carried by civilians were sideswords, primarily designed for cutting, but the evolution of duelling arts steadily transformed these weapons into long but thin-bladed swords with complex hilts to protect the hand. Today, we usually call them rapiers. While there is no clear-cut definition of a rapier, nor any neat historical dividing line to designate at what point the rapier had entirely evolved out of the sidesword, specialized duelling swords recognizably different from common sideswords became common during the latter half of the sixteenth century, and remained in use until the early eighteenth.

In addition to its place as a duelling weapon, the rapier carried an important social function in Early Modern Europe. Any proper gentleman wore a rapier as part of formal dress: a basic symbol of his martial training and prowess as a gentleman, and of his readiness to participate in duels should the need arise. This practice was within the limits of social acceptability so long as it was done by men of the right social class. Other swords used in war—as well as any defensive accoutrements, when worn on the same occasions— would imply that the wearer was looking to pick a brutal street fight. This practice of wearing rapiers continued for about a century.

In the the second half of the seventeenth century, duels to the death fell out of fashion in favour of duels to first blood, prompting a somewhat modified form of the rapier called the smallsword to replace its predecessor. With most duels no longer as dangerous as they were, the complex, protective hilts of the rapier vanished in favour of a simple hilt with minimal hand protection. Otherwise, however, the wearing of smallswords continued in the same fashion amongst European gentlemen until in the middle of the eighteenth century, when the non-military formal wearing of swords fell out of fashion entirely.

In the the second half of the seventeenth century, duels to the death fell out of fashion in favour of duels to first blood, prompting a somewhat modified form of the rapier called the smallsword to replace its predecessor. With most duels no longer as dangerous as they were, the complex, protective hilts of the rapier vanished in favour of a simple hilt with minimal hand protection. Otherwise, however, the wearing of smallswords continued in the same fashion amongst European gentlemen until in the middle of the eighteenth century, when the non-military formal wearing of swords fell out of fashion entirely.

While the works of Bolognese master Achille Marozzo (1484-1553) had a great influence on the development of Italian rapier-fighting systems, the first work that many today consider to be significantly devoted to the rapier (or a very late form of the duelling sidesword immediately preceding it) is the Treatise on the Science of Arms with a Philosophical Dialogue (Italian: Trattato di Scientia d'Arme con un Dialogo di Filosofia) by Camillo Agrippa (fl. 1553). This seminal work sets forth the model of a novel fighting system with the familiar four guards of later rapier fighting and the form of lunges. Agrippa's work also includes a profound body of fencing theory based on mathematical and geometrical principles. By the turn of the seventeenth century, systems of rapier fighting were well established, and other masters like Salvator Fabris (1544-1618) and Ridolfo Capoferro (fl. 1610) continued to elaborate on the techniques and theory that Agrippa had established. Their influence not only informed classical Italian fencing, but as some of these masters travelled elsewhere in Europe, they also spurred the development of rapier-fighting systems in other countries.

See more about learning how to use the rapier on our Programs page.

The term 'longsword' includes a gamut of long- and broad-bladed straight swords that can be wielded in one hand or two. The techniques of the longsword serve equally well in duels (one-on-one fighting) as well as on the battlefield. This weapon was largely popularized in story through Arthurian legends, historical epics, and modern fantasy books, movies, and television such as The Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones.

The term 'longsword' includes a gamut of long- and broad-bladed straight swords that can be wielded in one hand or two. The techniques of the longsword serve equally well in duels (one-on-one fighting) as well as on the battlefield. This weapon was largely popularized in story through Arthurian legends, historical epics, and modern fantasy books, movies, and television such as The Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones.

Though many often consider the longsword to be a brutish and simple weapon suited for hacks and slashes, it is in fact a sophisticated sword capable of much of the same finesse of its lighter counterparts, the rapier and the sidesword.

The system of longsword fencing taught at Academie Duello shares equal time between the cut and the thrust, and emphasizes circular movement, power generation, how to win ‘crossings’ of the sword, and feeling and responding to an opponent’s position, pressure, and timing.

The Anatomy of the Longsword

The longsword is a long, straight-bladed weapon with a simple crossbar and grip that can accommodate two hands. The overall length of a typical longsword ranges from 40" to 50", with blades varying in length between 30" and 40". Longsword weights vary but typically fall between 3 and 5 lbs.

The longsword is a long, straight-bladed weapon with a simple crossbar and grip that can accommodate two hands. The overall length of a typical longsword ranges from 40" to 50", with blades varying in length between 30" and 40". Longsword weights vary but typically fall between 3 and 5 lbs.

The Nature of the Longsword

Longsword combatants take rapid steps back and forth, keeping a safe distance while maintaining threat. Opponents with their blades circle tightly, looking for advantage and control of their adversary's weapon. The tap and slide of steel on steel mixes with the rustle of footwork until one fighter lunges—a blur, confident in position and timing.

Longsword combatants take rapid steps back and forth, keeping a safe distance while maintaining threat. Opponents with their blades circle tightly, looking for advantage and control of their adversary's weapon. The tap and slide of steel on steel mixes with the rustle of footwork until one fighter lunges—a blur, confident in position and timing.

The longsword is a two-handed weapon: one hand applies pushing force, the other a pull on the pommel to utilize leverage. Powerful movements of the entire body, always moving in circles and figure-eights, contribute to the weapon's tremendous cutting force. The opposing sides come together in dynamic crossings, always seeking to gain an advantage.

The longsword has been described as 'the great equalizer': while applications of pure force can work against an opponent, technique, speed and dexterity will triumph. Often sacrifices must be made on one area in order to capitalize in another. For instance, cuts from the shoulder convey the greatest strength but the slowest speed, whereas incredibly fast wrist cuts lack the force required to do serious damage.

History of the Longsword

During the course of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the knight's sword underwent a number of significant changes that produced not only a weapon that was light, large and highly versatile, but also a new system of armed combat to exploit the new features that the improved sword—the longsword—could offer. For several centuries prior, the knight's sword had been a single-handed, broad-bladed weapon about 36" that was capable of powerful slashes. New improvements in armour in the form of metal plates, however, were reducing the effectiveness of slashes, as they could turn aside a sharp edge without much difficulty. To overcome the new armour technology, both the blade and the grip of the knight's sword gradually increased in length, resulting in a weapon about 44" long. Moreover, the blade's shape steadily changed, becoming gradually thinner down its length and ending a sharp point. Thus, the longsword emerged into history, as swordsmiths pushed forging technology to its limits to produce weapons capable of defeating opponents clad in plate armour, which would eventually cover almost the entire body by the turn of the fifteenth century.

The spread of the Spatha longsword and plate armor throughout Europe in the Late Middle Ages also gave rise to new and sophisticated fighting systems. The longsword's overall length meant that a wielder could keep a greater distance from an opponent and therefore remain safer. Powerful slashes remained an important forte of the longsword, but the new blade's shape also permitted equally powerful thrusts against armoured opponents, which could penetrate unprotected areas of the body or weak spots in the armour.

The spread of the Spatha longsword and plate armor throughout Europe in the Late Middle Ages also gave rise to new and sophisticated fighting systems. The longsword's overall length meant that a wielder could keep a greater distance from an opponent and therefore remain safer. Powerful slashes remained an important forte of the longsword, but the new blade's shape also permitted equally powerful thrusts against armoured opponents, which could penetrate unprotected areas of the body or weak spots in the armour.

With the longsword's versatility exploited in the fighting systems that emerged in the Late Middle Ages, it is little wonder that this spatha sword became one of the most common weapons in Europe, not only amongst knights and the social elite, but amongst common soldiers and even civilians as well. The weapon lent itself equally well to the battlefield as it did to tournament melees. Common use persisted well into the sixteenth century, and survived as late as the seventeenth, when the longsword use eventually died out against the popularity of dueling swords. But the period of 1350 through 1600 nevertheless produced a wealth of combat manuals that cover the euorpian longsword in detail and describe sophisticated fighting systems that explore the vast possibilities offered by the weapon.

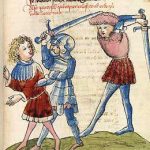

The first combat manuals that describe longsword usage date to the late fourteenth century: one of the most notable is a treatise by German master Johannes Liechtenauer dated to 1389 (MS 3227a). The earliest Italian manual describing longsword use is Fiore dei Liberi's Flower of Battles (or Flos Duellorum), dated to about 1410, of which at least three manuscripts remain extant. This text provides the main foundation for Academie Duello's longsword curriculum, with its detailed descriptions and illustrations. Somewhat later Italian texts that cover the longsword include Filippo Vadi's On the Art of Swordplay (De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, 1482-3) and Achille Marozzo's New Work on the Art of Arms (Opera Nova dell'Arte delle Armi, 1536).

Learn more about studying the use of the longsword on our Programs page.

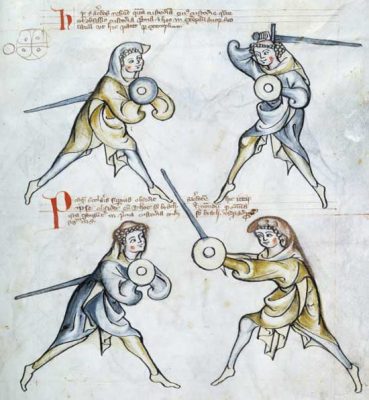

The primary system of sword and shield at Academie Duello derives from the fencing masters of Northern Italy and employs the sidesword, a single-handed renaissance cutting sword with a complex hilt to protect the hand, combined with a small metal shield known as a buckler. The modern term sidesword is a translation of the Italian spada da lato.

The primary system of sword and shield at Academie Duello derives from the fencing masters of Northern Italy and employs the sidesword, a single-handed renaissance cutting sword with a complex hilt to protect the hand, combined with a small metal shield known as a buckler. The modern term sidesword is a translation of the Italian spada da lato.

The techniques of single-handed sword and shield blend the cut and thrust, as well as control with both the sword and buckler to form an intricate and ambidextrous form. The student of the single-handed sword and shield will explore how to control a fight where an opponent keeps their weapon withdrawn, and how to use provocations, deceptions, circular movement and combinations of attack and defence.

Study of the sidesword starts at the scholar level of both the longsword and rapier streams of the Adult Swordplay program.

The Anatomy of the Sidesword

The sidesword is the sword typically used at Academie Duello for general sword and shield practice. However, we also employ use of the arming sword, the medieval predecessor of the sidesword. Both Munich sidesword and arming swords typically reach from 35" to 40" in total length with blade lengths varying from 30" to 38". They are broad-bladed, capable of both thrusts and cuts. They typically weigh between 2 and 4 lbs.

The sidesword is the sword typically used at Academie Duello for general sword and shield practice. However, we also employ use of the arming sword, the medieval predecessor of the sidesword. Both Munich sidesword and arming swords typically reach from 35" to 40" in total length with blade lengths varying from 30" to 38". They are broad-bladed, capable of both thrusts and cuts. They typically weigh between 2 and 4 lbs.

The arming swords of the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance are simple cruciform (or cross-shaped) swords. In contrast, the Sidesword duel is sometimes called a cut-and-thrust rapier because it has a thinner blade than the arming sword and a similar hilt design to late-renaissance rapiers called a swept hilt, (bands of metal stemming from the crossguard, 'sweeping' around the grip). There are other kinds of straight-bladed single-handed swords of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries like the Scottish broadsword that have broad blades like arming swords as well as basket hilts that cover the entire wielding hand.

The Nature of the Sidesword

The sidesword is a single-handed weapon suited to both battle situations with multiple opponents as well as one-on-one duels.

The sidesword is a single-handed weapon suited to both battle situations with multiple opponents as well as one-on-one duels.

Sidesword fighters meet a special challenge. Like advanced rapier students, they usually employ a ‘secondary’ in their other hand. While in rapier fighting it will most often be a dagger, with the sidesword it will be a shield. This requires the ability to use a small shield and move with the sidesword to protect the vulnerable hand and forearm behind it.

What the sidesword loses in length it makes up in versatility. Close proximity in combat restricts the use of the longsword and rapier, but not so the sidesword, which can strike much closer than its longer cousins and from nearly every direction. Cuts are diversified, like the longsword, to come from the shoulder, elbow or wrist.

The History of the Sidesword

The Western single-handed sword is an ancient weapon, tracing its history from Bronze-Age Mesopotamia, Palestine and Egypt, and through the Classical Periods of Greece and Rome. Although sometimes used to slash, it was very often used for thrusting. While the medieval single-handed sword that eventually gave rise to the arming sword is related to these ancient swords, it evolved primarily from the longer swords of the Celtic and Germanic peoples of Northern Europe, which were used mainly for slashing. By the Early Middle Ages, the single-handed sword had acquired a broad blade about 29" long, and in time, the sword also acquired a crossguard to better protect the wielder's hand, and developed into a cross-shaped (or cruciform) weapon. It became the choice sword of the knight's arsenal by the High Middle Ages, usually accompanied by a large shield in the other hand.

The Western single-handed sword is an ancient weapon, tracing its history from Bronze-Age Mesopotamia, Palestine and Egypt, and through the Classical Periods of Greece and Rome. Although sometimes used to slash, it was very often used for thrusting. While the medieval single-handed sword that eventually gave rise to the arming sword is related to these ancient swords, it evolved primarily from the longer swords of the Celtic and Germanic peoples of Northern Europe, which were used mainly for slashing. By the Early Middle Ages, the single-handed sword had acquired a broad blade about 29" long, and in time, the sword also acquired a crossguard to better protect the wielder's hand, and developed into a cross-shaped (or cruciform) weapon. It became the choice sword of the knight's arsenal by the High Middle Ages, usually accompanied by a large shield in the other hand.

During the thirteenth century, the longsword began to emerge from the single-handed sword as a larger, two-handed weapon that could more easily overcome new developments in armour. Nevertheless, the arming sword did not vanish from use, as fighting men recognized the usefulness of a lighter and smaller weapon in melees, accompanied by a shield or a second weapon in the other hand. The shape of the arming sword's blade, too, developed in the same way that the longsword did, tapering to a sharp point, making it effective against armoured opponents.

Arming-sword combat is extensively depicted in the first extant Western combat manual, Royal Armouries Manuscript (MS) l.33, dated to c. 1300. It is also found in the works of Italian masters Fiore dei Liberi (1409) and Filippo Vadi (1482-3). While the arming sword lent itself well to the battlefield, it also grew in popularity amongst civilians for personal protection in the rapidly growing cities of the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance. The weapon was in turn given treatment in combat manuals designed for civilian use, such as Achille Marozzo's The New Work on the Art of Arms (Italian: Nova Opera dell' Arte delle Armi, 1536).

The sidesword evolved out of the arming sword during the course of the sixteenth century. Since it was not always convenient to wear armour outside of battle, new protective features appeared on the hilt: sweeping bands of metal designed to protect the wielding hand from harm when in danger of an opponent's attack. Some sideswords steadily acquired a thinner blade to facilitate a more effective thrust. By the latter half of the sixteenth century, these sideswords would evolve into a weapon purely designed for duelling: the rapier. However, the sidesword itself was not displaced by this new weapon, remaining in popular use into the early seventeenth century.

Military use of single-handed swords continued throughout the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth in some areas, such as the Scottish Highlands, were the broadsword enjoyed widespread use. These swords acquired similar protective features to the hilt as the sidesword with the decline of armour in the seventeenth century. Still, the martial techniques associated with them largely hearkened back to the medieval arming sword.

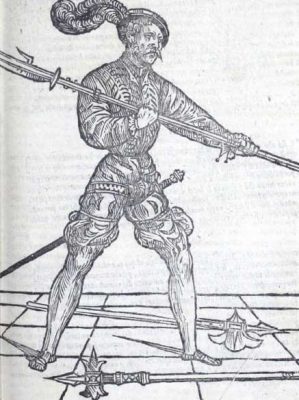

'Pole-weapon' (or 'polearm') is a general term for any weapon made up of a shaft or pole that usually has an offensive metal head at one end for thrusting, piercing, hacking or snagging. While the spear is the most well-known and most ancient member of this category, many other pole-weapons exist as well. With a remarkable diversity in size, the shape of their heads and martial usage, these pole-weapons include such weapons as the poleaxe (or pollaxe), halberd, bardiche, pike, partisan and bill, amongst many others.

'Pole-weapon' (or 'polearm') is a general term for any weapon made up of a shaft or pole that usually has an offensive metal head at one end for thrusting, piercing, hacking or snagging. While the spear is the most well-known and most ancient member of this category, many other pole-weapons exist as well. With a remarkable diversity in size, the shape of their heads and martial usage, these pole-weapons include such weapons as the poleaxe (or pollaxe), halberd, bardiche, pike, partisan and bill, amongst many others.

Pole-weapons also include the invaluable quarterstaff, a simple civilian weapon used for self-defence as well as country competitions. The quarterstaff is perhaps best known as the choice weapon of Little John of Robin Hood fame. It is this pole-weapon on which we focus much of our attention at Academie Duello. Not only is the quarterstaff relatively safe with its blunt ends, it is also extensively described in many historical fighting manuals as an excellent way to learn the basics of all pole-weapon techniques.

The Anatomy of the Quarterstaff and Pole-Weapons

Quarterstaffs are cylindrical rods about 1.5 to 2.5 inches thick, usually turned from a hardwood like ash, oak or hickory. There are two general sizes of quarterstaff: a short variety, ranging from 6 to 9 feet, and a long, ranging from 12 to 16 feet. Both are studied at Academie Duello. Quarterstaffs of both sorts sometimes have ends that have been sharped to points or fixed with metallic points similar to a spearhead.

Other pole-weapons vary in length considerably, from some just under 5 feet to pikes reaching upwards of 18 feet. The shapes of their heads also vary considerably depending on their function, but most have a blade, point, barb, beak, hammerhead or some combination of any of the above.

The Nature of the Quarterstaff and Pole-Weapons

The quarterstaff is best suited to unarmoured combat, whereas a number of other pole-weapons like the poleaxe are intended for combat in full armour.

The quarterstaff is best suited to unarmoured combat, whereas a number of other pole-weapons like the poleaxe are intended for combat in full armour.

The offensive range offered by a pole-weapon, although much greater than that of a sword, also has its disadvantages. Greater distance from an opponent offers protection, but the weapon can only create threat if its head has enough range and space to connect. If an opponent comes close enough, the length of the pole-weapon becomes a liability. Because of the length of their shafts, pole-weapon techniques emphasize both thrusts and sweeps in arcs, as well as coordination of momentum in order to strike effectively with a head (or end, simply, with a quarterstaff). As such, we practise both holding pole-weapons like the staff at one end to emphasize thrusting and powerful blows, as well as in the middle (half-staffing) to facilitate use of both ends of the staff. Using the two ends in coordination is an especially important element of pole-weapon fighting in order to deflect an oncoming attack with one end while garnering momentum for a stroke or thrust with the other.

Specific pole-weapons may emphasize certain thrusts or strokes more than others depending on the shape of their head, if designed for puncturing, snagging or hacking.

The History of the Quarterstaff and Pole-Weapons

Medieval and renaissance polearms combine two separate technologies. One is the spear, one of the oldest weapons (and technologies) in human history and a prominent arsenal in most Western armies throughout Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. The other is the assortment everyday tools used by medieval peasants, most of which are designed for agricultural activities, like pruning and reaping, but also boring and hammering. The result is a deadly combination in a range of weapons that comprise blades, barbs and spikes and a long reach that considerably influenced the nature of warfare throughout the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Medieval and renaissance polearms combine two separate technologies. One is the spear, one of the oldest weapons (and technologies) in human history and a prominent arsenal in most Western armies throughout Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. The other is the assortment everyday tools used by medieval peasants, most of which are designed for agricultural activities, like pruning and reaping, but also boring and hammering. The result is a deadly combination in a range of weapons that comprise blades, barbs and spikes and a long reach that considerably influenced the nature of warfare throughout the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Most pole-weapons did not become common until the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, but a few date back to the Early Middle Ages, such as some long-shafted axes, or even to Classical Antiquity, like the trident. The development and proliferation of pole-weapons in the High and Late Middle Ages came as a response to the domination of the European battlefield by heavy cavalry in the form of mounted knights. As infantry of the time could not hope to stop a heavy-cavalry charge or pierce heavy armour with shorter melee weapons, they began using pole-weapons in large formations to prevent such tactics. Additionally, the blades and points of their pole-weapons proved extremely effective at stopping mounted knights by impaling them or their horses outright, or by snagging a piece of plate armour and knocking or dragging them to the ground. Even if sharp edges on some pole-weapons could not penetrate high-quality plate armour, the hardened points on others were capable of puncturing some weak spots where the steel was thinner, or inflicting blunt trauma with a hammer-like head.

From at least the latter half of the fourteenth century, even knights had realized the power of pole-weapons, and they, too, began to train in them in addition to common soldiers for battle (still fully armoured) on foot. Pole-weapons also came to be used by knights in tournaments and judicial combats. Most of the combat manuals that we possess today reflect this knightly training in pole-weapons like the poleaxe, which remained a staple of the knight's arsenal into the sixteenth century alongside swords and the lance. This fact is attested by Italian combat manuals from the early fifteenth century onwards, which include prominent sections on pole-weapon combat as well as on swordplay.

The quarterstaff is mentioned in fighting manuals as early as the fifteenth century, but considering the simplicity of the weapon, it likely dates to a much earlier period. The term quarterstaff is, however, only attested from the late sixteenth century; earlier terms for the weapon include the 'two-handed staff' or simply 'staff'. The English master George Silver (c.1560-c.1620), an author of two treatises on martial arts, describes a 'short staff' and a 'long staff', corresponding to the two general sizes of quarterstaff.

Hema Polearms remained prominent items in the arsenals of European armies and warriors for centuries. They did not decline as judicial weapons until the early seventeenth century, when the rapier became the choice weapon of duellists. On the battlefield, some pole-weapons remained in use as late as the early nineteenth century (particularly in navies), but most largely declined after the proliferation of the bayonet in the closing years of the seventeenth century.

The Academie Duello system closely incorporates unarmed and close weapons work with modern knives and medieval daggers. The core focus of our unarmed system is learning good body mechanics, developing connection with the ground, and broadening your martial base for future weapons work.

The Academie Duello system closely incorporates unarmed and close weapons work with modern knives and medieval daggers. The core focus of our unarmed system is learning good body mechanics, developing connection with the ground, and broadening your martial base for future weapons work.

Our unarmed skills are based within the system of Fiore dei Liberi. The goal of the system is to get the opponent onto the ground as swiftly and effectively as possible without going there yourself. Techniques include throws, holds, joint locks, breaks, binds, and disarms. As our system is developed for dealing with multiple opponents and for use in battlefield situations, ground fighting is generally avoided.

Our system of wrestling emphasizes:

Control of the centre – Work at your own centre where you are strongest, move the opponent away from their own strength, and control the centre of the fight.

Opportune Striking – Use strikes to points of pain to eliminate advantages of size and strength.

Breaking structure – Use strikes and holds to break your opponent’s connection to the earth.

Taking space – Occupy your opponent’s space to eliminate their martial options.

Grappling training is featured in both the longsword and rapier streams of our adult swordplay programs.